- Safeguarding Client Funds: Oklahoma attorneys must keep client money in a dedicated trust account (IOLTA) separate from firm funds, with interest benefiting the Oklahoma Bar Foundation. Strict rules prohibit commingling and mandate that unearned fees, retainers, settlement proceeds, and other client funds be deposited into an IOLTA trust account.

- Compliance Best Practices: Law firms should implement detailed recordkeeping (individual client ledgers, monthly three-way reconciliations) and strong oversight. Common pitfalls like commingling funds, failing to reconcile, or “borrowing” from the trust account can lead to serious discipline. Regular internal reviews, staff training, and legal-specific accounting software help prevent violations.

- Enforcement & Consequences: The Oklahoma Bar Association (OBA) monitors trust accounts through required reports and bank overdraft notifications. Roughly 9% of disciplinary grievances involve trust accounting issues. Real-world cases show that even unintentional mismanagement—like using client funds to pay firm expenses—can result in suspension or worse. Adhering to Oklahoma’s trust accounting rules protects your clients’ money and your law license.

Introduction: Trust Accounts and IOLTA in Oklahoma

Every law firm in Oklahoma that handles client money must navigate IOLTA (Interest on Lawyers’ Trust Accounts) and trust accounting rules. These regulations exist to protect clients’ funds and maintain public trust in the legal profession. For small and mid-sized law firms, understanding Oklahoma’s specific trust account requirements is crucial—not only to avoid ethical violations, but also to run a healthy practice. Mishandling client trust funds can lead to disciplinary action, financial penalties, and even loss of your license. On the flip side, when managed correctly, trust accounts ensure you have funds on hand for fees and expenses, improving cash flow and reducing collection headaches (since retainers are paid up front).

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explain the key Oklahoma rules on lawyer trust accounts, including IOLTA requirements from the Oklahoma Bar Association (OBA) and Oklahoma Bar Foundation (OBF). We’ll cover practical compliance procedures, recordkeeping standards, and reporting obligations. We’ll also highlight common pitfalls (with real examples from Oklahoma disciplinary cases) and offer best practices to stay on the right side of the rules. This guide is structured with clear sections and actionable tips, and we’ve included an FAQ at the end to address common questions. Let’s dive in.

What Is IOLTA and Why It Matters in Oklahoma

IOLTA stands for Interest on Lawyers’ Trust Accounts. It’s a program established in the 1980s that allows interest from client trust accounts to be pooled and used for the public good (typically funding legal aid and justice programs). In practical terms, an IOLTA account is a pooled, interest-bearing trust account that law firms use to hold client funds that are nominal in amount or short-term in duration.

Under Oklahoma law, any client or third-party funds you hold in connection with legal representation—retainers, advance fee deposits, settlement monies awaiting distribution, filing fees given in advance, etc.—must be kept separate from your law firm’s own money. Client funds go into a trust account until they are earned by the lawyer or disbursed to the appropriate party. Importantly, Oklahoma requires that all pooled client trust accounts be set up as IOLTA accounts (interest-bearing accounts) with the interest automatically remitted to the Oklahoma Bar Foundation. In other words, you can’t keep interest on client funds; it either goes to the client (for substantial, long-term funds placed in a separate account) or to the Bar Foundation’s IOLTA program (for small or short-term pooled funds).

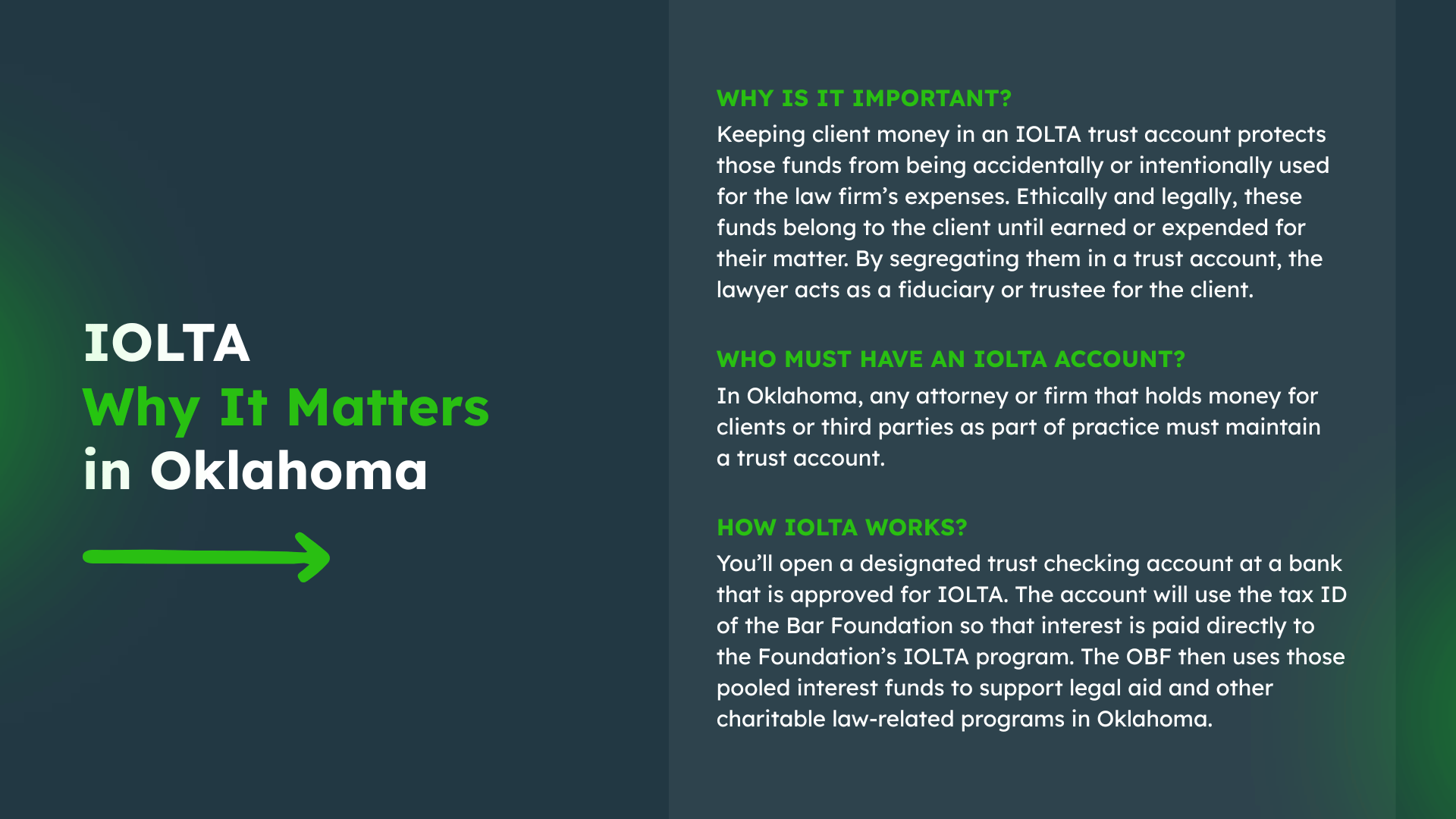

Why is this important? Keeping client money in an IOLTA trust account protects those funds from being accidentally or intentionally used for the law firm’s expenses. Ethically and legally, these funds belong to the client until earned or expended for their matter. By segregating them in a trust account, the lawyer acts as a fiduciary or trustee for the client. This builds client confidence and avoids even the appearance of impropriety. In fact, misusing client funds is one of the gravest ethical violations – it is often considered misappropriation or even theft, and it’s a leading cause of disciplinary action against lawyers. Placing client funds into a law firm’s operating account prematurely can result in large fines and potential disbarment. Thus, Oklahoma’s IOLTA rules are in place to ensure lawyers handle client money with utmost care and transparency.

Who must have an IOLTA account? In Oklahoma, any attorney or firm that holds money for clients or third parties as part of practice must maintain a trust account. The Oklahoma Bar Association makes participation in IOLTA mandatory for all lawyers who handle client funds. The only attorneys exempt are those who never receive or disburse client funds in advance – for example, if you only bill after completing work (so you never hold unearned fees in trust) or you’re a government lawyer/judge not in private practice. If you truly do not handle client funds, you can certify that to the Bar and you won’t need an IOLTA. But for the vast majority of private practice firms (even solo practitioners who take retainers), an IOLTA trust account is a must.

How IOLTA Works: You’ll open a designated trust checking account at a bank that is approved for IOLTA (most common banks offer IOLTA accounts – the OBF provides a list or can guide you). The account will use the tax ID of the Bar Foundation so that interest is paid directly to the Foundation’s IOLTA program. From the lawyer’s perspective, you don’t get to touch the interest – it’s automatically calculated and sent to the OBF (usually the bank does this remittance). The OBF then uses those pooled interest funds to support legal aid and other charitable law-related programs in Oklahoma. It’s essentially a way to make productive use of interest that would be too small to practically allocate to individual clients. (If a client deposits a very large sum or for a long period such that it could earn net interest for the client even after bank fees and administrative costs, then ethically that money should not be kept in IOLTA. Instead, set up a separate interest-bearing trust account for that client’s benefit. Oklahoma’s rules say only “nominal or short-term” funds go to IOLTA. In borderline cases, you should analyze the amount, expected duration, and costs to decide if a separate account is appropriate.)

Oklahoma’s Trust Accounting Rules and Requirements

Oklahoma’s rules for trust accounting are embodied in the Oklahoma Rules of Professional Conduct (ORPC) Rule 1.15 (“Safekeeping Property”) and related regulations. Here are the key requirements and what they mean for your law firm:

- Segregation of Client Funds: You must hold client or third-party funds in a separate account apart from your own funds. This is usually titled “Client Trust Account” or “Attorney IOLTA Trust Account” in the bank’s records, under the lawyer or firm’s name. Do not deposit client money into your business operating account. Likewise, don’t deposit your personal or firm money into the client trust account, except for one narrow exception (next point). Commingling (mixing) your funds with client funds is strictly prohibited. Example: If a client hands you a $5,000 retainer for future services, that goes into the trust account, not your operating account, because it’s not earned yet. Conversely, if a client pays an invoice for fees you’ve already earned, that payment should go directly to your operating account – putting earned fees into trust would be commingling (your money doesn’t belong in the client trust account).

- Allowed Minimal Firm Funds in Trust: The only time your own funds can be in the trust account is a small amount to cover bank charges or maintain a minimum balance. Oklahoma, like most states, permits lawyers to deposit a de minimis amount of firm money to pay service fees or avoid account closure for falling below a minimum balance. Typically, this might be on the order of $100 or whatever the bank requires to keep the account open and cover monthly fees. You should document this deposit as firm funds for bank fees. Aside from that, no other personal or firm money should sit in trust. You cannot “park” your income in the trust account for convenience or tax timing purposes – once fees are earned, they must be promptly removed from the trust account.

- What Must Be Deposited into Trust: Any funds that belong to the client, or are held for the benefit of the client, or to pay third parties on the client’s behalf, go into the trust account. Common examples include: unearned legal fees (advance retainers, flat fees paid upfront before work is done); advance payment of expenses (e.g. a client gives $500 to cover filing fees or depositions – you hold it in trust until you incur and pay those costs); settlement funds received that will be distributed to the client and possibly third parties (and from which you might eventually withdraw your contingent fee); and any other third-party funds you are holding (for example, money that is due to a client’s lienholders). The guiding principle: if it’s not your money (until earned or allocated by agreement), it belongs in the trust account.

- When to Disburse or Transfer Funds: Funds should remain in trust only until they are properly disbursed. If it’s an earned fee, you should transfer that amount to your operating account promptly upon earning it and providing any required billing/notice to the client. Oklahoma expects lawyers to withdraw fees only as earned or expenses only as incurred. Do not leave earned fees sitting in trust indefinitely – that would mean client money and your money are co-mingled. Conversely, do not withdraw money that hasn’t been earned or authorized – taking unearned funds out of trust is conversion. For example, if you bill a client from their retainer, you would move the billed amount from trust to operating, ideally contemporaneously with sending the invoice or as agreed in your fee contract. Always document any such transfer (ledger entry showing which client’s funds were withdrawn, for what invoice or purpose, etc.). If you’re holding settlement funds, only disburse them according to the settlement agreement – typically, you’d issue checks to the client, to your firm for fees (as agreed), and to any third-party with a legal interest (e.g. medical providers, liens) from the trust account. Never use one client’s money to pay another client’s obligation. Each client’s funds are to be treated separately within your records, even though they may be in one pooled bank account.

- OBA Trust Account Certificate & Reporting: Uniquely in Oklahoma, attorneys must report their trust account to the Bar Association and keep that information up to date. Under Rule 1.4 of the Rules Governing Disciplinary Proceedings, every OBA member must file a Trust Account Certificate identifying where their trust account is held (bank name, account number, etc.) or declare that they do not maintain a trust account (with the reason, e.g. not in private practice). New lawyers usually submit this when they get licensed, and established lawyers should update the Bar within 30 days whenever they open, close, or change a trust account. This reporting is confidential, but failure to comply can itself be grounds for discipline. Practical tip: Make sure when you set up your IOLTA that you also complete any enrollment forms required by the OBF (they have an IOLTA compliance statement to send to the Bar Foundation) and report the account to the OBA. It’s an often overlooked step for new firms.

- Approved Financial Institutions & Overdraft Alerts: Oklahoma’s program requires that your trust account be held in a bank that has agreed to certain reporting requirements. Notably, the bank must notify the OBA Office of General Counsel if any trust account check is presented against insufficient funds (overdraft). This includes any IOLTA account. Essentially, if you bounce a trust account check or have a shortfall, the Bar will find out about it. The OBA might then send you a letter asking for an explanation of the overdraft. (In many cases a one-time overdraft might be due to bank error or a minor mistake and can be explained – e.g. you deposited a check that bounced. As long as no client lost money and you corrected the error, it may not result in discipline. However, multiple overdrafts are a serious red flag.) To facilitate this, when you open an IOLTA, you and the bank sign an agreement for overdraft reporting to the OBA. Bottom line: Always monitor your trust balance to avoid overdrafts – if a check would overdraw the account, don’t let it clear. It’s far better to prevent an overdraft than to have to answer to the Bar after the fact.

- Accurate Records and Ledgers: Oklahoma requires lawyers to keep detailed records for all trust account transactions. This includes a general ledger for the trust account (checkbook register) recording every deposit, withdrawal, and the running balance. In addition, you must maintain individual client ledgers – a separate record for each client matter that shows all funds held on behalf of that client and every transaction affecting those funds. At any given time, you should be able to look at your books and answer: “How much money am I holding for Client X? And does the total of all client balances equal the current bank account balance?” If your recordkeeping is up to date, the sum of all client ledger balances plus any firm funds for bank fees will equal the overall trust account balance. Oklahoma’s Rule 1.15 and general accounting principles demand this three-way reconciliation of (1) the bank statement balance, (2) your checkbook register balance, and (3) the total of all client sub-account balances. It’s wise (and usually required) to reconcile these every month. We’ll discuss reconciliation more in the best practices section.

- Retention of Records: You must keep all trust account records for at least five years after the termination of a representation (i.e. after the case or client matter is closed). This retention period is specified in ORPC 1.15. In practice, you should keep: bank statements, canceled checks (or digital copies), deposit slips, client ledger cards or printouts, receipts for any withdrawals, invoices or billing statements tied to trust disbursements, settlement statements, fee agreements, and any reconciliations or reports you’ve done. Essentially, you need a paper trail to justify every penny in and out of the trust account. If a question ever arises (by a client or the Bar), you may have to produce these records to show that you handled funds correctly. Failing to maintain complete records is itself an ethical violation. An easy habit: scan and save everything to a secure digital file for each client and for the account, or use legal accounting software that keeps an audit trail.

- Disputed Funds or Unclaimed Funds: If there’s a dispute over funds in trust (for example, both the client and a third-party like a doctor’s office claim part of a settlement), the rule is to keep the disputed portion in the trust account until the dispute is resolved. Release any portion that is not in dispute. For the disputed amount, don’t unilaterally decide – hold it until the interested parties reach an agreement, or there is a court order/arbitration decision on it. Similarly, if you can’t locate a client to return money that belongs to them (say you have a refund or remaining balance and the client disappears), Oklahoma law provides a path: first, attempt to find the client and consider the Unclaimed Property Division of the State Treasurer for truly abandoned funds. If that doesn’t apply, the Oklahoma Bar Foundation will accept the unclaimed client funds and hold them (with interest) for safekeeping. You’d send the funds to OBF with a letter explaining whose money it is, last known address, and your efforts to contact them. If the client later reappears, OBF will refund the principal to you so you can return it to the client. This ensures you don’t improperly keep client money that isn’t yours, and it doesn’t languish in trust forever.

- No Misuse of Trust Funds: It should go without saying, but you cannot use client trust money for your own purposes. Do not borrow from the trust account, even “just until a settlement comes in” or to cover an office expense in a pinch. Taking advances on unearned fees or using funds designated for one purpose to pay for something else is treated as either conversion or misappropriation of client funds – serious offenses. For instance, you cannot decide to pay your firm’s rent out of the client trust account, even if you plan to replace it later. There’s an Oklahoma ethics opinion and common sense rule: money in trust is not a personal loan facility for the lawyer. In one Oklahoma disciplinary case, an attorney admitted he used client trust funds to cover payroll and office bills during a rough patch – he was suspended for 30 days and could easily have faced harsher punishment. Even “innocent” misuse (like mistakenly withdrawing too soon) must be corrected immediately. If you ever realize you withdrew funds in error (say you thought a fee was earned but the work wasn’t completed), you should replace the money to the trust account right away and document what happened to show you corrected the error. Good procedures (and a bit of caution) will prevent such mistakes in the first place.

By adhering to these rules, Oklahoma lawyers fulfill their fiduciary duty to clients. Next, we’ll outline practical steps and best practices to help your firm manage the trust account correctly and efficiently.

Compliance Best Practices for Law Firm Trust Accounting

Following the letter of the law is important, but day-to-day compliance requires establishing good practices within your firm. Here are some best practices and procedures to ensure your Oklahoma trust account is handled properly:

1. Use a Dedicated Trust Account (IOLTA) for All Client Funds: Open a separate IOLTA trust checking account solely for client funds. Do not mix client money with your operating funds at any time. Make sure the account’s checks and deposit slips are clearly labeled “Trust Account” or “IOLTA Account” to avoid confusion. Pro tip: Also consider having checks in a distinct color for trust, so you or staff don’t accidentally use the wrong checkbook. This physical separation reinforces the ethical separation.

2. Institute Detailed Recordkeeping: Maintain a manual or software-based ledger system that tracks the trust account meticulously. At minimum, set up: (a) a general trust account register (like a checkbook register logging every transaction in chronological order), (b) individual client ledgers for each matter, showing funds held for that client and all credits/debits, and (c) a way to keep copies of supporting documents (receipts, copies of checks, deposit records). For each transaction, record the date, amount, source or payee, and client matter description (“Received $1,000 retainer from John Doe for case #1234” or “Paid $300 filing fee for Jane Client – check #1001”). Keeping notes on each entry helps if you later need to explain it. Modern practice management software or legal-specific accounting software can automate a lot of this and reduce errors by linking transactions to client matters. The key is that at any given moment you should know exactly how much each client has in trust and why.

3. Perform Monthly Three-Way Reconciliations: Reconcile the trust account every month without fail. This means comparing three things – the bank statement balance, your internal trust account balance, and the total of all client ledger balances – and making sure they all match to the penny. If they don’t, find out why immediately. For example, if the bank balance is higher because a check hasn’t cleared yet, note that outstanding check. Or if your records missed a bank fee, you’ll see a discrepancy – then record the fee in your ledger (and perhaps replenish the account with firm funds to cover it). Regular reconciliation is not only required by good accounting practice, but it’s your early warning system for mistakes or theft. Many trust fund misappropriations have been caught (or could have been caught) by a monthly reconciling process. Oklahoma Bar officials strongly encourage monthly reconciliation and even surprise reconciliations if you suspect an issue. Document each reconciliation (save a PDF or printout) and keep it in your records. If you use software, export the reconciliation report monthly.

4. Implement Internal Controls & Oversight: Even in a small firm, it’s wise to have checks and balances for trust accounting. If you have staff handling deposits or writing trust checks, make sure no single person has unchecked control. For instance, some firms require two signatures on trust checks above a certain amount, or the lawyer must approve all trust disbursements. At minimum, the responsible attorney must review the trust account statements and records personally every month. Do not delegate away all oversight. The Bar has seen cases where an unwatched bookkeeper or even a well-intentioned assistant made errors or thefts that went unnoticed because the lawyer never looked at the bank statements. Had those lawyers been reviewing their trust accounts, they could have prevented or caught the problem early. Make it a routine: when the bank statement (or online statement) comes in, the managing partner or solo attorney looks it over, compares to the reconciliation, and signs off. This also ties into securing login credentials – ensure only appropriate people can access the account and that there’s a separation between those who handle bookkeeping and those who review it, if possible.

5. Educate Your Team and Delegate Cautiously: If you assign trust accounting tasks to a paralegal, bookkeeper, or office manager, train them in the basics of Oklahoma’s rules. Many law firm employees may not know the strictness of trust account regulations. Make sure they understand that accuracy is paramount and that even a small mistake can have big consequences for the firm and the attorney’s license. Emphasize no one may ever “borrow” from trust or adjust entries to make things look balanced when they’re not. As the attorney, remember that you retain ultimate responsibility for the trust account’s integrity. The OBA has said this is a non-delegable duty – you can be disciplined for trust account violations even if a staff member actually committed the error or theft, because you must supervise and have proper controls. Choose trustworthy employees and implement oversight. Many firms run background checks on any employee who will handle money (one Oklahoma lawyer learned too late that their bookkeeper was a convicted felon for theft). Trust, but verify.

6. Use Legal-Specific Accounting Tools: While you can keep trust records with basic tools (even a spreadsheet or paper ledger), using software designed for law firm trust accounting can greatly reduce errors. The OBA’s Management Assistance Program has identified and even negotiated discounts for trust accounting solutions. For example, the OBA endorses products like TrustBooks (a lawyer-centric trust accounting app) and LawPay (an online payment processor that correctly handles credit card deposits to trust). Practice management software like LeanLaw (with deep QuickBooks integration) can automate three-way reconciliations and prevent common mistakes – for instance, it won’t let you overdraw an individual client ledger, which generic accounting software might allow. These tools often include built-in reports that make compliance easier (like generating a report of each client’s balance). While not mandated by the Bar, such software can act as a safety net. If you prefer to use QuickBooks or another general accounting program, be extra careful: set it up correctly for trust accounting (perhaps consult resources like Using QuickBooks for IOLTA Trust Accounting from the OBA) and consider using class or sub-account features to track client funds separately. Always double-check that the software isn’t allowing things that violate trust rules (for example, QuickBooks might not stop you from writing a trust check that exceeds the balance – you have to be the backstop).

7. Plan for Bank Fees and Prevent Overdrafts: One common pitfall is bank charges hitting the trust account and causing a negative balance. To avoid this, find out what fees your bank charges (monthly service fees, check order fees, etc.) and ensure you keep a small cushion of firm money in the account to cover them. Keep an eye on those charges each month. If a fee or a mis-timed deposit could trigger an overdraft, proactively transfer some firm money in. Remember, an overdraft will get reported to the OBA automatically, so it’s not just a private matter. It’s far better to maintain a buffer and never have an overdraft than to explain to the Bar “why your trust account bounced a check.” Also, never bounce a check to a client or third-party – that obviously damages your reputation and the client’s interests. If a deposit (like a client’s check) is still clearing, do not disburse those funds yet unless you are certain it’s cleared or you have other funds to cover it in case it bounces. Essentially, treat the trust account with the same caution you would a personal account that can never be in the red – because it can’t.

8. Document Everything and Be Ready to Report: Maintain a file (physical or digital) of all trust account documents. Have copies of all account opening forms, OBF IOLTA enrollment forms, OBA trust account certificates, etc. Each time you update the Bar with new account info, keep a copy of what you sent. This way, if there’s ever a question or audit, you can quickly show that you have been in compliance with reporting requirements. Similarly, document any client consent needed for trust actions. For example, if you apply a client’s trust funds to an invoice, you should have a clause in your engagement agreement that authorizes you to do so (after invoicing or notification). If you ever need to take an unusual step, like using funds for a different purpose with client permission, get that permission in writing. (By default, you shouldn’t use funds for any purpose other than what they were intended for; even with permission it can be risky, so generally avoid it to be safe.) Good documentation practices also mean if a client or regulator asks for an accounting, you can swiftly provide a clear report.

By incorporating these best practices, your firm will create a strong culture of compliance around trust accounting. It may seem like extra work, but it’s an essential part of law practice management – and it can save you from nightmares down the road. As the OBA’s Ethics Counsel Travis Pickens succinctly advised: at any time, you should be able to “reconstruct, account and justify all amounts that flow through your trust account” – that’s the gold standard to aim for.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even well-meaning lawyers can run into trust accounting trouble if they’re not careful. Here are some common pitfalls seen in Oklahoma (and nationwide), along with tips on how to avoid them:

- Commingling of Funds: This is the #1 cardinal sin of trust accounting – mixing client money with the lawyer’s money. Commingling can happen in subtle ways. For example, you might finish a case and have earned the fee, but forget to move the money out of trust for a few months – during that time, your earned money is sitting with unearned client funds (commingled). Or you might pay a small firm expense out of the trust account, thinking “I’ll replace it later” – even briefly using client funds is commingling (and actually conversion). Avoid it: Be disciplined about moving earned fees to your operating account promptly (and only after they’re earned/invoiced). Likewise, never pay personal or firm expenses directly from trust – always transfer your earned fee first, then pay expenses from the operating account. If you need to refund a client or pay a third-party, those payments come straight from the trust account. Keep a little ledger for any firm funds in trust (for fees) so you know how much of the account is your money (ideally a constant small number). If you see more in trust than the total of client balances, that’s a red flag you might have commingled something inadvertently.

- Misappropriation (Using Client Money for Wrong Purpose): The most egregious violation is taking client funds for yourself or uses other than the client’s matter. Some attorneys who face financial pressures have rationalized “borrowing” from the trust account to keep the office afloat, intending to pay it back. This is a huge mistake. The Oklahoma Supreme Court and disciplinary board treat misappropriation as extremely serious – often warranting suspension or disbarment. For instance, an Oklahoma lawyer who used funds that were supposed to go to estate heirs to instead pay his office bills was suspended and publicly censured. In another case, a lawyer was found to have converted client settlement money (though it was deemed “simple conversion” rather than outright theft, he still got a multi-year suspension). Avoid it: The simple rule – it’s not your money. View the trust account as sacrosanct. If you wouldn’t take money out of a client’s wallet without permission, don’t take it out of their trust funds either. Set a firm policy that no one in the firm (lawyer or staff) ever withdraws trust funds except for proper client-related payments or approved transfers of earned fees. If you catch yourself even considering using trust money “just until that big payment comes in,” stop and seek another solution (e.g., a line of credit or even closing the firm – anything but misusing client funds). It’s that serious.

- Failure to Reconcile / Ignoring the Account: Some lawyers get busy and assume the trust account “takes care of itself.” This is dangerous. Not reconciling monthly means you could miss errors or theft for long periods. In one cautionary tale (shared in an OBA article), a lawyer’s trusted secretary embezzled over $250,000 from the trust account over five years – in part because the lawyer never reviewed the statements or reconciliations. By the time it came to light, clients had complained and the damage was done. Avoid it: Reconcile every month and review the details. If you see any odd transactions (unknown charges, checks you don’t recall signing), investigate immediately. Many banks now provide images of checks in statements – look at them. If something doesn’t add up, act promptly. It’s much easier to fix an issue when it’s a month old than years later when you have a catastrophe. Cultivate a mindset that your trust account is active, not “set and forget.”

- Overdrafts and Accounting Errors: Simple arithmetic mistakes or timing issues can cause an overdraft. Writing a check from trust when a deposit hasn’t cleared yet, or forgetting about an automatic monthly bank fee, can put the account in the red. Because banks must report trust account overdrafts to the Bar, even an innocent error creates a disciplinary headache. Avoid it: Keep a cushion of your own funds in the account for fees (as allowed). Before writing any check, double-check the client’s balance and the overall balance. Use accounting software that warns of low balances. Also, consider linking the trust account to an alert system – for example, get notified if the balance dips below a certain threshold. If you ever do accidentally overdraw (say a client’s check bounces after you’ve disbursed funds), immediately deposit replacement funds from your firm to cover the shortfall and notify the OBA’s Office of General Counsel with an explanation if required. Prompt, honest action can be the difference between a slap on the wrist and a more serious outcome, especially if the cause was a math error or bank delay. Still, strive never to be in that position.

- Client Ledger Mistakes (Deficit Balances): Another common pitfall is accidentally using money from Client A to pay for Client B’s needs. This happens if you’re not diligently tracking individual ledgers. For example, if Client A has $500 in trust and you erroneously pay a $600 invoice for them, you’ve not only overdrafted the account $100, you’ve likely dipped into other clients’ money to cover that extra $100. This means some other client’s funds were used without authorization. Avoid it: Always check the specific client ledger before approving a disbursement for that client. It can help to use software that will prevent you from writing a check that exceeds that client’s balance. If doing it manually, maintain a habit: look at the client’s balance first. If a client needs to pay an expense that will exceed what they have on deposit, get additional funds from the client first or pay from your operating and treat it as a client receivable (depending on the situation and rules). Never “borrow” from Peter’s retainer to pay Paul’s filing fee.

- Lax Security and Unauthorized Access: Trust accounts can be tempting targets for fraud, both internal and external. If multiple people have check-writing authority, or if your checks or debit card are not secured, you risk theft. We’ve talked about internal embezzlement, but also consider external fraud: keep your trust account info safe from phishing emails or hackers (who could try fraudulent wire transfers or ACH debits). Avoid it: Limit who is authorized at the bank. Many firms don’t allow debit cards on trust accounts to prevent easy cash withdrawals. Store checkbooks in a locked drawer. If an employee leaves, change online banking passwords immediately and alert the bank to remove them from access. Review canceled checks – if you ever see a check number out of sequence or payee you don’t recognize, don’t shrug it off.

- Not Understanding the Rules / Lack of Training: Some attorneys (especially new solos) simply aren’t well-versed in trust accounting and can inadvertently violate rules. For example, an attorney might think it’s okay to take a fee out of trust because they “worked a lot this month,” not realizing that unless they’ve billed the client or completed the work per the agreement, it’s still unearned and must stay in trust. Or they might not realize they need to file the trust account certificate with the Bar. Avoid it: Make use of the resources from the Oklahoma Bar – the OBA offers ethics advice, articles (like this one!), and even trust accounting CLE courses. When in doubt, you can call the OBA Ethics Counsel for guidance on a tricky trust question. Taking a few hours to educate yourself and your staff can prevent a world of trouble. It’s much easier to learn the rules proactively than to defend yourself in a disciplinary proceeding later.

By being aware of these pitfalls and actively guarding against them, you significantly reduce the risk of a trust account violation. Many compliance failures are due not to intentional misconduct, but to neglect or sloppy practices. As one OBA practice advisor noted, simple negligence accounts for many trust account violations. The good news is that simple diligence can prevent them. In the next section, we’ll look at how Oklahoma monitors trust accounts and some real-world examples of enforcement, which underscore why all these precautions truly matter.

Enforcement, Audits, and Real-World Examples in Oklahoma

Oklahoma’s legal regulators take trust account compliance very seriously. The OBA’s Office of General Counsel (OGC) and the Professional Responsibility Commission (PRC) are charged with investigating and disciplining attorneys for ethical violations – and misuse of client funds is among the top issues they watch for. Let’s explore how enforcement works and highlight a few illustrative cases:

Bank Reporting & OBA Oversight: As mentioned, Oklahoma banks that hold IOLTA accounts have to report any trust account overdrafts to the OBA. When OBA’s OGC receives an overdraft notice, they typically open a file and send a letter to the attorney requesting an explanation. You’ll need to show whether the overdraft was a bank error, a bookkeeping mistake, or something more serious. In many instances, if it truly was a minor mistake and no client lost money, the OGC may not pursue formal discipline – but the incident will be on record. If overdrafts happen repeatedly or the explanation is unsatisfactory, it can trigger a deeper investigation. The OGC has the ability to perform a trust account audit or demand records from you to ensure everything is in order. Remember, by holding out as a lawyer, you implicitly agree to these oversight mechanisms as part of the license to practice.

Random Audits: In some jurisdictions, bar authorities do random compliance audits of law firm trust accounts. Oklahoma does not appear to routinely do random audits on a broad scale, but the OBA can audit if they have reason to suspect issues (for example, if a grievance is filed about finances or multiple overdrafts occur). To that end, always be prepared to open your books to the Bar if asked. If your records are immaculate and clearly show every transaction, an audit will go much smoother and you’ll likely satisfy the inquiry. Conversely, if you can’t produce proper ledgers or justify transactions, the auditors will dig deeper. An audit can lead to further action if it uncovers violations.

Client Grievances: Often, enforcement starts with a client complaint. A client who feels their money was mishandled or not promptly paid out can file a grievance. For example, a client might complain that after their case settled, they didn’t receive their money for a long time – prompting the Bar to ask the attorney, “Why the delay? Where are the funds?” If the attorney had improperly used those funds or commingled them, it will come to light. According to OBA statistics, trust account issues are a notable cause of grievances. In one recent annual report, the OBA PRC noted that about 9% of formal grievances opened involved trust account violations, plus an additional 4% were triggered specifically by trust account overdraft notices. That means roughly one in eight disciplinary investigations had something to do with mishandling client funds. Only neglect and misrepresentation were larger categories. The lesson: if you mishandle trust money, there’s a decent chance you’ll end up on the Bar’s radar.

Disciplinary Outcomes: The consequences for trust accounting violations in Oklahoma range from mild to severe, depending on the facts. In relatively minor cases – say a one-time bookkeeping error with no client harm – an attorney might receive a private reprimand or be required to take additional trust accounting education (the OBA may divert some cases to a diversion program for training when the issue seems to stem from ignorance or negligence rather than malice). However, if client funds were actually misappropriated or a pattern of problems emerges, public censure, suspension, or disbarment are all possible. The Oklahoma Supreme Court decides ultimate discipline in serious cases, and they look at factors like the amount of money, whether it was intentional, and if the client was harmed.

Let’s look at a few real-world Oklahoma examples to illustrate the stakes:

- Misappropriation & Suspension (2019): In State ex rel. OBA v. Brandon Duane Watkins (2019), a lawyer was found to have engaged in conversion and misappropriation of client funds among other misconduct. He had multiple counts of mishandling money, including taking funds that should have been held for a client. The Oklahoma Supreme Court, after de novo review, deemed it “simple conversion” but nonetheless suspended him for two years and one day. This case shows that even if the Court believes the lawyer didn’t act with venal intent (hence “simple” conversion, perhaps indicating negligence), the discipline was still career-impacting. A suspension of two years and a day means the lawyer must apply for reinstatement and prove fitness, not just wait out time. The Bar and Court send a clear message: taking client money is unacceptable, and even lesser forms of mismanagement can end your practice for an extended period.

- Using Trust Funds for Expenses (2024): In State ex rel. OBA v. David Leo Smith (2024), an attorney received settlement funds that were supposed to be distributed to heirs in a probate matter. Before he paid the clients their shares, he paid himself a fee and even paid another lawyer a referral fee, and then allowed the balance to dip below what was owed to the clients. Evidence showed he used some of the clients’ settlement money to cover his firm’s payroll and bills during a financially challenging period. The trust account balance fell well below the amount that should have been held for the clients, essentially meaning he spent their money for non-client purposes. In mitigation, this lawyer eventually implemented better bookkeeping and took CLE courses in trust accounting, and the amount was later replenished. The disciplinary trial panel recommended a relatively lenient outcome, and the Oklahoma Supreme Court ultimately issued a 30-day suspension. While this was a short suspension, it’s still a public discipline on record. It reinforces that even short-term or “borrowed” use of client funds is a violation. The attorney was punished even though he fixed his accounting later – because for a time, his clients’ money was not where it should have been.

- Negligence and Supervision Failures: Although not an Oklahoma case, an example often cited in ethics CLEs (and mentioned in the Oklahoma Bar Journal) is the California lawyer whose assistant embezzled $265,000 from the trust account over five years. He wasn’t intentionally stealing client funds himself, but his lack of oversight allowed it to happen. He trusted one person to handle everything and never verified the records. The end result: clients were hurt, the lawyer had to repay a huge sum, and he faced bar discipline (suspension) despite being a victim of the theft, because he violated his duty to safeguard client property. The takeaway: “Simple oversight and minimal diligence would have prevented this lawyer’s problem”. Oklahoma attorneys should heed this warning—being honest isn’t enough; you must also be diligent.

- Frequent Overdrafts – Red Flags: Another scenario that can lead to trouble is if your trust account repeatedly has issues, even if no one complaint stands out. The OBA’s annual reports indicate that dozens of overdraft notices are received each year (for example, 96 overdraft notices were received in 2017). The OBA can and does monitor these. If a lawyer is chronically sloppy—perhaps repeatedly bouncing checks but covering them after the fact—the Bar may decide to investigate proactively. It’s much better to correct course after the first mistake than to become a statistic. If you get an inquiry from the OBA about your trust account, take it seriously and use it as an opportunity to improve your practices (often the OBA will expect you to demonstrate changes like attending a trust accounting class or adopting new procedures).

In summary, Oklahoma’s enforcement of trust accounting is robust. The combination of client complaints, bank overdraft alerts, and required attorney reporting creates a safety net to catch problems. As a lawyer, you want to be on the right side of that equation—proactively compliant rather than reactively trying to explain a deficiency. The real-world cases underscore a final point: no client matter or amount of money is worth risking your license. Clients trust you with their funds, and the Bar demands that trust be honored with exacting care. The rules may seem strict, but they ultimately protect everyone: the client’s money is safe, and you protect your reputation and ability to practice.

Conclusion

Trust accounting in Oklahoma might seem complex at first, but with knowledge and good habits, it becomes a routine part of running a law practice. Small and mid-sized law firms, in particular, should view trust compliance not as a burden but as part of delivering professional service. When clients hand you their money to hold, you’re stepping into a fiduciary role. By diligently following Oklahoma’s IOLTA and trust account rules, you build client confidence, avoid disciplinary risks, and ensure the financial health of your firm.

Remember, the key principles are straightforward: Keep client funds separate, track every penny, and don’t touch those funds except as allowed. Use the tools at your disposal – whether that’s a detailed spreadsheet or modern practice management software – to stay organized. Reconcile regularly and never ignore warning signs. When in doubt, err on the side of safeguarding the funds (for instance, leaving money in trust a bit longer until you’re sure it’s earned, rather than pulling it out too soon).

Oklahoma provides plenty of guidance to help lawyers stay compliant. The OBA’s Management Assistance Program and Ethics Counsel have published articles, FAQs, and even personal assistance if you need to set up your trust accounting right. Take advantage of those resources. It’s also wise to periodically review your trust procedures (for example, each year or whenever your firm undergoes a change like staff turnover or new software). Make “trust accounting check-ups” a normal part of your firm’s operations, similar to how you’d review your financials or insurance coverage.

By following the best practices outlined in this guide – from segregation of funds to proper recordkeeping and oversight – you will substantially reduce the likelihood of mistakes. Your firm can then reap the benefits of trust accounts (like upfront retainers improving cash flow and client service) without stumbling into trouble. In fact, a well-managed trust account can be a selling point to clients: it shows you are responsible and trustworthy with their money.

In the end, compliance is not just about avoiding punishment; it’s about upholding the integrity of your practice. As the saying goes, “take care of your clients’ money as carefully as you would your own” – actually, even more carefully, since your professional livelihood depends on it. With careful attention and the right systems in place, Oklahoma law firms of any size can master IOLTA and trust accounting. Stay vigilant, stay informed, and your trust account will remain a source of confidence rather than concern.

FAQ: Oklahoma Trust Accounting and IOLTA

Q1: When do I need to open an IOLTA trust account for my law firm in Oklahoma?

A: You need an IOLTA trust account if you will hold any client or third-party funds in the course of your practice (e.g. retainers, advance fee payments, settlement funds awaiting distribution). Oklahoma requires all attorneys in private practice who handle client funds to participate in the IOLTA program. So, as soon as you anticipate receiving money that isn’t yours to keep (even a $500 retainer), set up a trust account.

The only time you might not need an IOLTA is if you never hold client money at all – for example, if you work on an after-the-fact billing model or you’re a government lawyer. In that case, you’d certify to the Bar that you don’t maintain a trust account. For everyone else, it’s mandatory to open a trust account. It’s wise to do this before you receive any client funds, so you’re not scrambling when that first retainer check comes in. Also, be sure to use a bank that offers IOLTA accounts (most do) and complete any enrollment forms required by the Oklahoma Bar Foundation.

Q2: What kinds of funds are supposed to go into the trust account, and what should not go into it?

A: Put simply, client funds go in trust; your earned funds stay out. More specifically, deposit all money that belongs to the client or a third party in connection with your representation into the trust account. This includes: advance fee retainers, flat fees paid upfront (until you earn them), money to cover costs (filing fees, etc.), settlement or judgment proceeds that you’ve received but not yet disbursed, and any funds where ownership is unclear or disputed (until resolved).

On the other hand, do not deposit your own money into trust except for a minimal amount to cover bank fees or maintain a minimum balance. So, payments of fees after you’ve billed the client (i.e. the client is paying an invoice for work already done) go straight into your operating account – those are earned funds, no longer client property. Similarly, if you receive a reimbursement (say the client pays you back for a filing fee you advanced from your own pocket), that repayment is yours, so it doesn’t need to touch the trust account.

Think of the trust account as a holding bin for other people’s money that you are temporarily stewarding. Anything that’s yours to keep should bypass trust and go to your firm’s account. And of course, never use the trust account as a personal slush fund or to store firm reserves – that’s commingling and is prohibited.

Q3: Can I use money from the trust account to pay my law firm’s bills if I replace it later?

A: No, absolutely not. You should never use client trust funds for any purpose other than what they’re designated for – even “borrowing” money for a short time is forbidden. Many attorneys have gotten in serious trouble for this kind of misappropriation. Even if you fully intend to pay it back when, say, a big check arrives next week, it’s unethical and considered misappropriation (or theft) of client funds.

The trust account is not a cushion for your firm’s cash flow. The correct approach if your firm has bills to pay is to use your own funds or a business line of credit – not your clients’ money. Withdrawals from trust should only happen to (a) pay clients, third parties, or expenses on the client’s behalf, or (b) transfer earned fees to your operating account after you’ve done the work and invoiced the client per your agreement.

If you take money out for any other reason, you’re crossing a bright red line. The disciplinary authorities in Oklahoma have suspended and even disbarred lawyers for using client money to run their office. It’s just not worth the risk. Tip: If you find your firm is struggling financially to the point of temptation, seek professional financial advice – but do not dip into the trust account.

Q4: What should I do if my trust account accidentally gets overdrawn or a check bounces?

A: First, act immediately to fix the shortfall. If a client’s deposit bounced or there was an accounting mistake, you’ll need to cover the negative balance right away, usually by moving funds from your operating account (this is one of the rare times you deposit firm money into trust – to replace a deficit caused by error). Next, understand that your bank will likely send an overdraft notice to the OBA’s Office of General Counsel.

The OBA may contact you asking for an explanation. Be honest and detailed in your response, and describe the corrective steps you took. If it was a simple error (say a math mistake or bank fee you didn’t anticipate) and you’ve corrected it and nobody was harmed, the OBA may note it and close the inquiry with perhaps a warning. However, if client funds were misused or it keeps happening, you could face discipline. Prevention is key: to avoid ever bouncing a trust check, always verify the client’s balance before writing checks, maintain a buffer for fees, and reconcile your account monthly (which helps catch bank errors or bounced client checks quickly).

If an overdraft happens due to a client’s bad check, you still have to make the trust account whole – you’ll then pursue the client for the money, but you can’t let the trust account stay in the red in the meantime. The Bar’s perspective is that it’s your duty to ensure client funds aren’t short, even if someone else’s error caused it. In summary: fix it fast, document what happened, report if required, and implement safeguards so it doesn’t happen again.

Q5: How long do I need to keep trust account records, and what exactly should I keep?

A: Oklahoma requires that you keep all trust account records for at least five years after the end of the representation (some lawyers choose six years to be safe, but five is the rule). The clock typically starts when the case or matter is concluded or the file is closed. The records you should retain include: bank statements, canceled checks (or digital images of checks) and check stubs, deposit slips, detailed client ledgers, your general trust ledger, monthly reconciliation reports, client instructions or letters related to funds, copies of invoices or bills corresponding to any withdrawals of fees, and any other documentation of transactions (like wire transfer confirmations or credit card processing reports for trust payments).

Essentially, if it’s a piece of paper or electronic record that substantiates a trust account entry, save it. It’s also wise to keep records of any communication with clients about their trust money (e.g., a letter to a client enclosing a refund check, or an email where the client approves using funds for a certain cost). Organized recordkeeping not only keeps you compliant with Rule 1.15, but will be a lifesaver if a question arises.

You should be able to go back years and reconstruct exactly what happened with a client’s money. Many firms scan everything and store it digitally (with backups) so that even after five years, nothing vital is lost. Remember, if the Bar audits you or a client questions a transaction years later, you’ll need these records to demonstrate that you handled their funds correctly.

Q6: How do I handle a situation where a client’s money is in trust, but I can’t find the client or they won’t respond to instructions on disbursement?

A: This can happen if, for example, a client disappears and you’re left holding settlement funds or an unearned fee that needs to be refunded. First, make all reasonable efforts to contact the client – certified mail to last known address, email, phone, even reaching out to emergency contacts if you have them. Document these attempts. If you truly cannot locate the client and a significant period has passed, Oklahoma law provides a couple of avenues.

One, check the Oklahoma Unclaimed Property Fund (State Treasurer’s Office) to see if you are required to remit the funds there – this usually applies if the funds meet the legal criteria for unclaimed property. If not (or in addition), the Oklahoma Bar Foundation (OBF) will accept the unclaimed client funds and hold them. You would send the money to the OBF IOLTA program with a cover letter explaining whose funds they are, the circumstances, the client’s last known contact info, and your attempts to reach them.

The OBF will hold those funds (and any interest accruing) in trust. If the client later comes forward, they can recover the money from OBF. This procedure ensures you don’t violate the rule against converting client property – you’re effectively handing off the responsibility to a safekeeper (OBF) when you cannot keep holding the funds in your trust account indefinitely. One thing you should not do is just pocket the money or move it to your operating account because the client vanished. It’s not yours.

Also, do not donate the money to charity or use it for another client – the safest path is through the OBF or Unclaimed Property channels as described. Before remitting to OBF, you can also call the OBA Ethics Counsel or OBF for guidance on the proper steps; they can confirm the process and any required paperwork.

Q7: Is special accounting software required for trust accounting compliance?

A: There’s no specific software mandated by the Bar – you won’t find a rule saying “Thou must use QuickBooks (or LeanLaw, or any product).” In fact, Oklahoma’s guidance acknowledges that any system – even a manual one – is acceptable if it accurately and completely accounts for client funds. That said, while you could use a notebook and calculator, it’s often risky and time-consuming to do this by hand without errors. Most law firms at least use spreadsheets or general accounting software, and many opt for legal-specific trust accounting software. The OBA encourages lawyers to use tools that help maintain compliance.

For example, practice management software or dedicated trust accounting programs will automate the three-way reconciliation, flag potential overdrafts, and keep a clear audit trail. These tools can significantly reduce the mental load of trust accounting, especially for small firms that don’t have a full-time bookkeeper. If you use generic accounting software (like standard QuickBooks), be cautious: it isn’t tailor-made for law firm needs and might allow commingling or ledger overdrafts unless you configure it very carefully.

You might consider consulting resources (the OBA has an article on using QuickBooks for IOLTA) or getting an accountant’s help to set it up. In short, while you aren’t required to buy special software, it’s wise to use some system beyond just pen-and-paper to track the detailed information. Whether that’s a robust Excel workbook or a cloud-based solution like LeanLaw or TrustBooks is up to you. The goal is to make compliance as foolproof as possible. Many small firm lawyers find that investing in the right software pays for itself by preventing costly mistakes and saving time.

Feel free to reach out to the Oklahoma Bar Association for more resources on trust accounting, or consult LeanLaw’s blog and guides for additional best practices on managing IOLTA accounts. With the right knowledge and tools, you can confidently manage your client trust account and keep your firm in excellent standing. Good luck, and happy (compliant) accounting!